1. Background

Academic procrastination is a pervasive issue among adolescents within educational settings, significantly impacting their academic trajectories (1). Examples include consistently delaying studying for exams until the last minute, repeatedly postponing writing assignments, or avoiding starting long-term projects despite looming deadlines. Defined as the irrational deferment of necessary tasks despite anticipating potential negative consequences (2), this behavior stems from deficits in decision-making, prioritization, planning, and plan adherence. Over time, procrastination can become an entrenched lifestyle pattern, where repeated avoidance behaviors solidify into automatic responses to academic demands. For example, a student who consistently puts off studying for small quizzes may develop a habitual pattern of delaying academic tasks, leading to chronic procrastination even for high-stakes exams (3). This pattern is linked to negative emotional states such as fatigue, monotony, and demotivation, which contribute to increased anxiety, depression, and diminished self-esteem, ultimately affecting academic performance and contributing to setbacks. This prevalent phenomenon disrupts academic tasks and daily routines, posing a substantial impediment to students’ academic achievement and overall success (4). While some delays may be intentional, academic procrastination is typically considered an irrational and detrimental form of postponement (5).

A key challenge for students experiencing academic procrastination is often a perceived lack of meaning in their studies (6). "Meaning in the academic domain" explores how students find value and significance in their education, extending beyond mere grade attainment to connecting learning with personal lives, goals, and beliefs (7). This sense of meaning fosters motivation and engagement (8), enabling students to discover direction and purpose, ultimately maximizing their potential. It involves active educational engagement and persistent effort towards personally relevant goals, rather than passive participation (9). Cultivating this sense of meaning can effectively counteract procrastination by providing the motivation to overcome delaying tendencies (10), encouraging ownership of learning through task commitment, responsibility acceptance, and project completion.

School belonging has been a consistent focus of research concerning students who procrastinate academically (6). School belonging is defined as the behaviors enabling a student to adapt to a specific activity or setting, thereby fostering a sense of connection to various individuals, subjects, and the school environment itself. These behaviors contribute to increased feelings of comfort and well-being, and a reduction in procrastination (11). When students feel a strong sense of belonging, they are more likely to perceive school tasks as relevant and valuable, leading to increased motivation and reduced procrastination. This is supported by studies showing that belonging fosters a sense of responsibility and accountability, making students more likely to follow through on academic commitments. This sense of belonging underpins an individual’s decisions regarding their interactions with their surroundings or specific issues (12). Furthermore, it facilitates collaboration and participation in social development. Therefore, belonging is a process through which individuals develop a sense of commitment and responsibility towards a place, object, or issue, generating positive feelings towards that entity (13). Korpershoek et al. (14) have demonstrated the positive effects of school belonging on academic achievement and increased engagement in school activities.

Equipping students with strategies to maintain focus during procrastination is crucial. Meaning-oriented training, a cognitive-behavioral intervention, effectively mitigates academic procrastination by targeting individual beliefs and behaviors (15). This approach posits that substantial educational change occurs between training sessions through individual practice and the application of self-regulation and behavioral techniques (16). Therefore, therapists must ensure adolescents fully understand the methodology, value, and importance of consistent practice for each technique (17). Like other skills, proficiency requires repeated practice. While each session introducing a new technique and therapist-guided practice can yield immediate, positive, yet potentially transient effects (18), this practical application fosters confidence in the positive changes resulting from sustained practice. Increased confidence, in turn, enhances motivation for continued practice, amplifying efficacy (19). Meaning-oriented training emphasizes the reciprocal interaction of cognition, affect, and behavior, facilitating client understanding of the thoughts and feelings influencing actions (20).

Core techniques include: (1) Cognitive restructuring, which helps students identify and challenge negative thoughts related to academic tasks, replacing them with more positive and realistic ones; (2) values clarification, which guides students in exploring their personal values and connecting them to their academic goals, thereby increasing motivation; (3) goal setting and planning, which teaches students how to break down large tasks into smaller, manageable steps and create realistic action plans; (4) mindfulness and relaxation techniques, which help students manage anxiety and improve focus during study sessions; (5) time management strategies, which provide students with tools to prioritize tasks and allocate time effectively. Key characteristics, including a strong therapeutic alliance, experiential and group processes, an active, goal-directed, and problem-focused approach, coping skill development, and feedback emphasis, make it highly suitable for client work. Grounded in a humanistic perspective of the healthy individual, with a focus on spirituality through self-reflection and connection with a higher power, this framework can impact a broad range of intrapsychic constructs. Meaning-oriented (academic) training, functioning as a self-regulation strategy, draws upon Iranian identity and historical principles, suggesting significant potential (15). Research has demonstrated its effectiveness in enhancing academic optimism and educational perception (21), as well as improving spiritual well-being and reducing anxiety (22).

Despite the growing body of research on academic procrastination and its interventions, there remains a gap in understanding how meaning-oriented training specifically impacts both sense of meaning and school belonging simultaneously in adolescents with procrastination tendencies. This gap is particularly evident in the lack of studies that examine the combined effects of these constructs on reducing procrastination and enhancing overall well-being. In light of the foregoing discussion and given the high prevalence of academic procrastination within school settings, especially among adolescents, coupled with its detrimental effects on the attainment of educational objectives and the emergence of various academic difficulties, research in this domain is both necessary and significant.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to investigate the efficacy of meaning-oriented training in enhancing both the sense of meaning and school belonging among students exhibiting symptoms of procrastination.

3. Methods

This study utilized a quasi-experimental control group design to examine the effects of an intervention. The target population comprised students in Dezful county exhibiting academic procrastination during the 2022 - 2023 academic year. To ensure adequate statistical power, an a priori power analysis using G*Power was performed, revealing that a sample size of 30 would sufficiently detect a significant effect (α = 0.05, power = 0.95). A convenience sample of 30 participants was recruited and then randomly assigned to either the experimental (n = 15) or control (n = 15) group. Random assignment was conducted using a random number table: Each participant was assigned a unique number, and then numbers were randomly selected to allocate participants to either the experimental or control group, minimizing selection bias.

Inclusion criteria were current high school enrollment, male gender, age between 16 and 18 years, a score exceeding 45 on a validated procrastination questionnaire, adequate physical and mental health for study participation, parental consent, and voluntary agreement to participate. Adequate physical and mental health was assessed through a self-report questionnaire that inquired about any current or chronic physical illnesses, recent hospitalizations, or current mental health diagnoses. Participants were excluded if they or their families withdrew cooperation at any point during the study, had a history of psychotropic medication use for childhood disorders, or missed more than two intervention sessions.

During the study, the control group participated in their regular classroom activities without any additional intervention related to the focus of study on meaning-oriented training. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and verified by their parents, emphasizing their right to withdraw from the study at any time. The confidentiality of all questionnaire data was assured, with a guarantee that information would not be disclosed to any external parties.

3.1. Procedure

Following ethical approval, three male high schools in Dezful were randomly selected from the available pool. Student academic records were then reviewed to identify those with a semester grade point average (GPA) below 14. These students were invited to an in-person information session where the study’s aims and procedures were detailed, and their participation was solicited. Participants were also administered a procrastination questionnaire. From this pool, 30 students scoring above 45 on the procrastination questionnaire were randomly selected for inclusion in the study.

The experimental group participated in a 10-week meaning-oriented training program, with each weekly session lasting 90 minutes. These sessions were facilitated by the first author. A summary of the meaning-oriented training program content is provided in Table 1. The control group received no intervention during the study period. A follow-up assessment was conducted 45 days post-intervention.

| Sessions | Content |

|---|---|

| 1 | Introduces the meaning-oriented academic training program, its benefits, and the roles of participants. It focuses on defining meaning and the process of meaning-seeking. |

| 2 | Explores various types of meaning and how to achieve it, emphasizing its role in life and introducing the concepts of flourishing and vitality. Thinking and meditating on meaning are practiced. |

| 3 | Focuses on self-meaning, choice, and the evolution of meaning, including resilience training and finding meaning in suffering. Social relationship development and purpose in pain are also covered. |

| 4 | Continues exploring the evolution of meaning, along with decentering, understanding life circumstances, and the relationship between meanings and attributes. Flow, contentment, and forgiveness are introduced. |

| 5 | Addresses harmful and conflicting meanings, emotional toxicity, and recognizing false meanings. Breaking the cycle of depression and the problems of flourishing are explained. |

| 6 | Focuses on maintaining and realizing meaning, enhancing spiritual intelligence, and changing attitudes. Ways of receiving and inventing meaning are explored. |

| 7 | Introduces meaning-oriented academic training and its characteristics, including improving family relationships in line with academic meaning. Academic flourishing and optimism are emphasized. |

| 8 | Continues meaning-oriented academic training, emphasizing faith in academic meaning, practicing in solitude, and self-compassion. Love for creatures, self-love, and gratitude are also covered. |

| 9 | Focuses on establishing a relationship with one’s meaning, creating, metacognition, and setting boundaries on thoughts. Planning, monitoring, and evaluation are covered. |

| 10 | Emphasizes strengthening willpower, responsibility, and optimism in pursuing academic meaning. The session concludes with post-testing and appreciation for participants. |

A Summary of the Meaning-Oriented Training Sessions

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. The Meaning of Education Questionnaire

The Meaning of Education Questionnaire, a comprehensive instrument developed by Henderson-King and Smith (23), measures students’ perceptions of the diverse significance of education. This 86-item questionnaire assesses ten distinct dimensions representing various student priorities and educational goals. Each dimension is scored independently, with higher scores indicating greater relative importance attributed to that specific meaning of education. Items are rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very low) to 5 (very high). A total score is calculated by summing all item scores, resulting in a possible range from 86 (minimum) to 430 (maximum). The instrument has demonstrated acceptable internal consistency, with a reported Cronbach’s alpha of α = 0.79 (24). In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess internal consistency, yielding a reliability coefficient of 0.76.

3.2.2. The Sense of School Belonging Questionnaire

The Sense of School Belonging Questionnaire, developed by Brew et al. (25), measures students’ sense of belonging within the school environment. The instrument comprises positively worded statements rated on a Likert scale ranging from "completely agree" to "completely disagree". It encompasses six subscales: Peer belonging, teacher support, fairness, safety, academic engagement, and broader community engagement. For the present study, the total scale score was utilized. Makian and Kalantar (26) reported a reliability coefficient of 0.88 for this instrument. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.83.

3.3. Data Analysis

Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using SPSS version 25 to assess changes in sense of meaning and school belonging across three time points: Pre-intervention, post-intervention, and follow-up. Significant main effects were followed up with Bonferroni-corrected post hoc tests to identify specific pairwise differences between time points.

4. Results

The study sample consisted of 30 students exhibiting symptoms of academic procrastination. The control group had a mean age of 16.85 years (SD = 2.39), while the experimental group had a mean age of 16.28 years (SD = 2.11). An independent samples t-test revealed no significant difference in age between the two groups. Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) for sense of meaning and school belonging for both the meaning-oriented training (experimental) and control groups across the pre-intervention, post-intervention, and follow-up assessments are presented in Table 2.

| Variables and Phases | Experimental Group | Control Group |

|---|---|---|

| Sense of meaning | ||

| Pre-test | 245.07 ± 26.35 | 249.53 ± 28.55 |

| Post-test | 293.73 ± 27.49 | 248.87 ± 28.35 |

| Follow-up | 281.93 ± 26.03 | 246.01 ± 26.64 |

| School belonging | ||

| Pre-test | 64.27 ± 12.61 | 64.87 ± 11.64 |

| Post-test | 83.47 ± 10.04 | 65.53 ± 11.34 |

| Follow-up | 78.07 ± 10.02 | 63.40 ± 10.66 |

Means and Standard Deviations of Sense of Meaning and School Belonging in Experimental and Control Groups Across Assessment Time Points a

In this study, the assumption of sphericity was violated; therefore, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied. Results from the repeated measures ANOVA (Table 3) revealed significant main effects of time for both sense of meaning (F = 365.55, P < 0.001, η2 = 0.89) and school belonging (F = 425.58, P < 0.001, η2 = 0.91), indicating improvements in both constructs across the assessment period for all participants. Significant time × group interactions were also observed for both sense of meaning (F = 86.78, P < 0.001, η2 = 0.80) and school belonging (F = 116.27, P < 0.001, η2 = 0.84), demonstrating differential rates of change between the experimental and control groups.

A significant main effect of group for sense of meaning (F = 8.19, P < 0.001, η2 = 0.28) indicated that the experimental group exhibited higher levels of sense of meaning compared to the control group, even at baseline. Similarly, a significant main effect of group for school belonging (F = 9.07, P < 0.001, η2 = 0.30) demonstrated that the experimental group, following the meaning-oriented training intervention, showed significantly greater school belonging than the control group, even after controlling for initial differences. These findings underscore the efficacy of meaning-oriented training in promoting both sense of meaning and school belonging among students exhibiting procrastination tendencies.

| Variables and Sources | SS | df | MS | F | P-Value | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sense of meaning | ||||||

| Time | 229.39 | 1.29 | 186.57 | 365.55 | 0.001 | 0.89 |

| Time × group | 108.91 | 1.59 | 68.50 | 86.78 | 0.001 | 0.80 |

| Group | 143.21 | 1 | 143.21 | 8.19 | 0.001 | 0.28 |

| School belonging | ||||||

| Time | 223.65 | 1.36 | 163.66 | 425.58 | 0.001 | 0.91 |

| Time × Group | 114.91 | 1.92 | 60.16 | 116.27 | 0.001 | 0.84 |

| Group | 268.01 | 1 | 268.01 | 9.07 | 0.001 | 0.30 |

Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance Results for Sense of Meaning and School Belonging

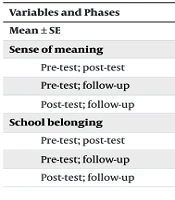

Bonferroni post hoc analyses revealed significant increases in sense of meaning scores within the experimental group from pre-intervention to both post-intervention and follow-up assessments (P < 0.001); conversely, no significant changes were observed in the control group at any time point. No significant differences in sense of meaning were found between the post-intervention and follow-up assessments in either group. Parallel findings emerged for school belonging: The experimental group demonstrated significant increases from pre-intervention to both post-intervention and follow-up (P < 0.001), while the control group showed no significant changes (Table 4).

| Variables and Phases | Experimental Group | Control Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SE | P-Value | Mean ± SE | P-Value | |

| Sense of meaning | ||||

| Pre-test; post-test | 48.66 ± 9.83 | 0.001 | -0.66 ± 10.35 | 0.958 |

| Pre-test; follow-up | 36.86 ± 9.56 | 0.001 | -3.52 ± 10.08 | 0.730 |

| Post-test; follow-up | -11.80 ± 9.78 | 0.238 | -2.86 ± 10.05 | 0.778 |

| School belonging | ||||

| Pre-test; post-test | 19.20 ± 4.16 | 0.001 | 0.66 ± 4.25 | 0.878 |

| Pre-test; follow-up | 13.80 ± 4.16 | 0.002 | -1.47 ± 4.08 | 0.721 |

| Post-test; follow-up | -5.40 ± 3.66 | 0.152 | -2.13 ± 4.02 | 0.600 |

Bonferroni Post Hoc Comparisons for Experimental and Control Groups Across Assessment Time Points

5. Discussion

This study investigated the impact of meaning-oriented training on sense of meaning and school belonging in students with procrastination tendencies. Results suggest that this training is effective in fostering a stronger sense of meaning among these students. Significant improvements in the experimental group following the intervention highlight its potential to address a core contributor to procrastination: A perceived lack of purpose and significance in academic tasks (15). This study demonstrates that meaning-oriented training enhances academic engagement by encouraging participants to explore personal values, align studies with individual goals, and contextualize their role within a broader worldview, thereby fostering deeper academic involvement. Consistent with prior research (20, 21), these findings underscore the pivotal role of meaning-making in bolstering motivation and well-being, with interventions targeting this construct yielding positive effects on academic behaviors and outcomes.

The implications for educational practice are notable: Incorporating meaning-oriented strategies into curricula or tailored interventions could mitigate procrastination by cultivating intrinsic motivation. This form of motivation — rooted in enjoyment, interest, and personal significance — shifts students’ focus from task-related discomfort to the inherent rewards of engagement, reducing avoidance tendencies. Consequently, intrinsically motivated students exhibit greater task initiation, persistence, and satisfaction, disrupting procrastination cycles and promoting proactive learning over reactive, externally driven responses.

This study demonstrated that meaning-oriented training effectively enhanced school belonging among students exhibiting procrastination tendencies. This finding is noteworthy given the established link between a strong sense of school belonging and positive academic outcomes, improved mental health, and reduced risky behaviors. Meaning-oriented training may strengthen students’ ties to their school community by fostering a connection to personal values and purpose (16). When students engage in meaning-making, they are more likely to perceive their academic environment as relevant and supportive. This sense of relevance fosters a stronger identification with the school, its values, and its members. When students find meaning in academic work, they are more likely to feel invested in their education and connected to the supporting school environment. This increased connection can create a positive feedback loop, further reducing procrastination by enhancing motivation, engagement (21), and a sense of responsibility towards the school community.

These findings have practical implications for educators and counselors. Implementing meaning-oriented interventions could foster not only academic motivation but also a greater sense of community and belonging. Creating opportunities for students to connect learning to personal values, explore aspirations, and engage in meaningful interactions can contribute to a more positive and supportive school climate, where students feel valued, understood, and connected. Meaning-oriented academic training promotes increased academic effort and deeper cognitive processing in students prone to procrastination, fostering ownership of academic activities and contributing to enhanced school belonging and a stronger sense of purpose (18). This training offers a pathway for individuals to discover meaning, particularly benefiting those experiencing existential frustration — a sense of emptiness, lack of purpose, and questioning of one’s existence and its value — and struggling to find a "reason to continue studying". Cultivating meaning empowers individuals to identify and overcome obstacles to personal agency, facilitating integration within the school context (17). Meaning-oriented academic training assists students in finding meaning within academic experiences and, through social support, adapting to sorrow, grief, limitations, and academic procrastination (18). This approach posits a singular root cause for various academic challenges: A lack of meaning in academic life, a principle with broad applicability (27).

This study’s methodological approach, employing convenience sampling and focusing on male high school students from Dezful county, presents limitations to the generalizability of its findings. The specific demographic focus restricts applicability to other populations, including female students, individuals from different geographic locations, and those in diverse educational settings. Furthermore, the cultural context of Dezful county, characterized by collectivist values, may have influenced the effectiveness of meaning-oriented training. In collectivist cultures, individuals may derive purpose from family and community goals, potentially impacting their perception of meaning and their response to interventions aimed at enhancing it. These factors, including both demographic and cultural specificity, limit the extent to which the study’s results can be generalized to broader populations.

5.1. Conclusions

This study examined the effectiveness of meaning-oriented training on sense of meaning and school belonging in students with procrastination tendencies. Results indicate that the training positively impacted both constructs, with significant differences observed between experimental and control groups post-intervention. The intervention addressed psychological factors linked to procrastination, such as a lack of purpose and school disengagement, while also fostering a more supportive school experience. This suggests that meaning-oriented approaches may mitigate negative consequences of procrastination, including anxiety and decreased academic performance. The findings highlight the potential of integrating such training into educational settings to promote adolescent well-being and academic success, particularly for students struggling with procrastination. Further research is recommended to explore long-term effects, mechanisms of influence, and moderators of treatment effectiveness, using larger, more diverse samples and longitudinal designs.